Response

In 2012, the Endowment began to engage rural churches in a multifaceted summer-learning intervention to improve literacy among elementary school students in their communities. The program used a three-pronged approach: recruiting students who need literacy intervention for a six-week reading camp; providing evidence-informed and data-driven instruction by highly qualified teachers; and staging weekly parent/caregiver events to engage families in the education process. Together, these strategies aimed to equip churches to play a measurable and effective role in the community, and to help close the literacy gap between rural students and their better-resourced peers.

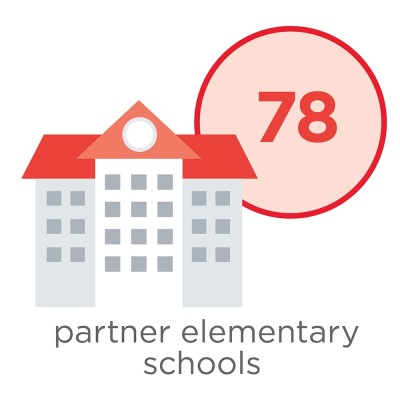

Endowment Trustees approved a one-year grant to a rural United Methodist Church in Iredell County, N.C., to test the program in the summer of 2013. Results were promising, and a second grant funded the program for additional summers. In 2014, the Endowment also began funding the program at Seaside United Methodist Church in rural Brunswick County.

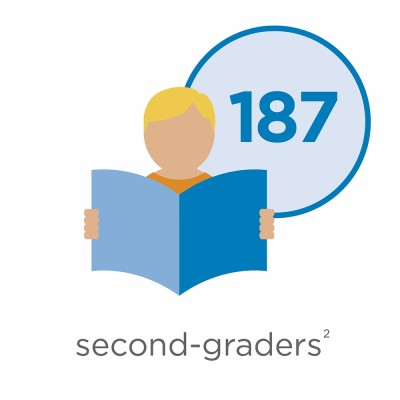

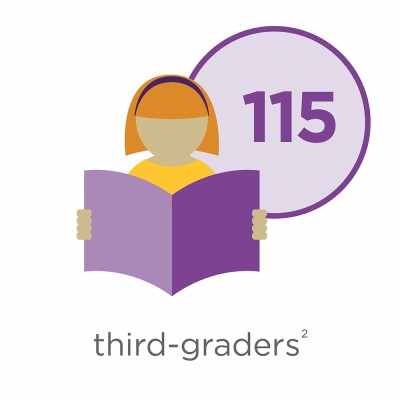

In 2018, a third rural United Methodist Church joined the summer literacy work. Nine additional churches joined the initiative in 2019; five more came on board in 2020. By the summer of 2024, the initiative had grown to 23 churches. Nearly 2,000 students have been served by these programs over the years.

Endowment-Supported Summer Programs

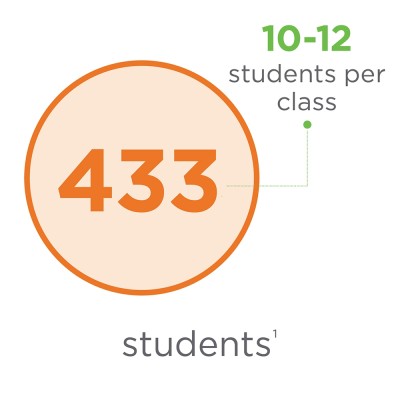

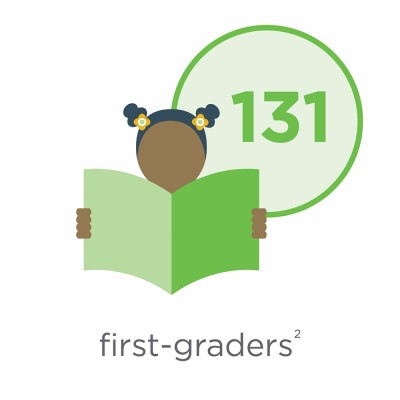

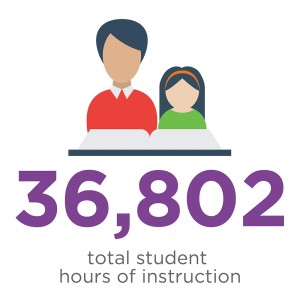

Since the Rural Church Summer Literacy Initiative contributes to the Endowment’s emphasis on the “zero to eight” population, funded churches each work with their local public schools and other community partners to recruit 24 to 48 kindergarten through second-grade students in need of summer literacy intervention. After recruitment, the program:

- Runs for four to six weeks in the summer, Monday-Friday, with full day programming

- Is hosted in church buildings

- Hires teachers who demonstrate excellent reading instruction

- Provides 80 – 90 total hours of reading instruction for during morning hours morning

- Offers afternoon enrichment activities each day

- Feeds a healthy breakfast and lunch to all students

- Wraps students in love and overcomes barriers to their participation and learning

- Engages parents/guardians through weekly workshops and other activities

- Contributes to the ongoing development of the program model through data collection, research activities, and participation in the statewide learning community facilitated by the Endowment